Waikiki is usually encountered as a destination before it is recognized as a neighborhood. For most visitors, it arrives prepackaged as a set of familiar images. High-rise hotels along the shoreline. Palm trees lining wide sidewalks. A warm ocean and a long stretch of sand. That version of Waikiki is not false. It is simply incomplete.

Behind the resort frontage exists a functioning urban district with residents, workers, schools, small businesses, and infrastructure that operates long after the beach chairs are stacked and the last tour bus leaves. People wake up here, commute from here, raise families here, and grow old here. Waikiki is not only something to visit. It is a place where daily life unfolds.

This tension between Waikiki as global symbol and Waikiki as lived environment has shaped the area for more than a century. Long before it became one of the most recognizable resort districts in the world, Waikiki was a landscape of wetlands, fishponds, agriculture, and royal retreat. What exists today is the result of layered transformations rather than a single moment of creation. Understanding Waikiki requires holding all of these identities at once.

Waikiki as a Neighborhood

Waikiki is usually described from the outside. The shoreline. The hotels. The shopping corridor. The beach activity. Those descriptions are accurate, but they describe only the surface. Behind that surface is a compact urban neighborhood that functions in much the same way as any other dense city district.

Thousands of people live here full time. They wake up early, commute, work long shifts, run errands, pay rent, and repeat the process day after day. Apartment towers rise behind resort properties. Residential hallways sit above retail storefronts. Clinics, schools, storage units, and small offices exist within blocks of beachfront hotels.

This layering creates a version of Waikiki that rarely appears in travel content. A person can move from a crowded lobby into a quiet residential corridor in seconds. A side street can feel almost ordinary while the main strip feels theatrical. Both realities exist simultaneously.

Living Inside a Place People Only Visit

Living in Waikiki means adapting to a place that was not designed around long-term residence. Infrastructure favors turnover. Short stays. High foot traffic. Constant movement. Residents learn which blocks stay quieter, which hours are tolerable, and which businesses remain consistent year after year.

For many, daily life becomes an exercise in carving out small pockets of normal inside a highly performative environment. Grocery shopping happens next to souvenir stores. Morning walks pass by tour buses idling in hotel driveways. Ordinary routines exist inside an extraordinary setting.

What Doesn’t Appear in Postcards

Postcards show leisure. They rarely show labor. Waikiki operates because of a massive workforce that cleans rooms, cooks meals, teaches lessons, maintains buildings, runs retail, staffs security, and keeps infrastructure functioning.

They also do not show older residents who remained in the area through decades of redevelopment, or families who adapt to rising costs by living in smaller units or shared housing. Waikiki’s population is fluid, but it is not empty. A core community persists even as everything around it changes.

Transients, Drifters, and the In-Between Population

Beyond tourists and long-term residents exists another large group that shapes Waikiki’s character. People who arrive with the intention of staying for a while, find work, share housing, and attempt to build some version of a life in Hawaiʻi, even if they are unsure how long they will last.

Some come chasing surf. Some come chasing weather. Some are escaping something back home. Some are simply curious. Many take jobs in hospitality, food service, retail, or construction. They live close to where they work because transportation is expensive and time-consuming.

This creates a constant cycle of arrival and departure. People form friendships knowing they may be temporary. Communities partially assemble and partially dissolve. For locals and long-term transplants, this churn can make lasting connections more difficult than in places where populations are stable.

Waikiki absorbs all of it. Visitors. Residents. Workers. Drifters. People trying to survive. People trying to start over. The neighborhood functions as a kind of human tide pool. Everything passes through. Some things remain.

The Ground Beneath Waikiki

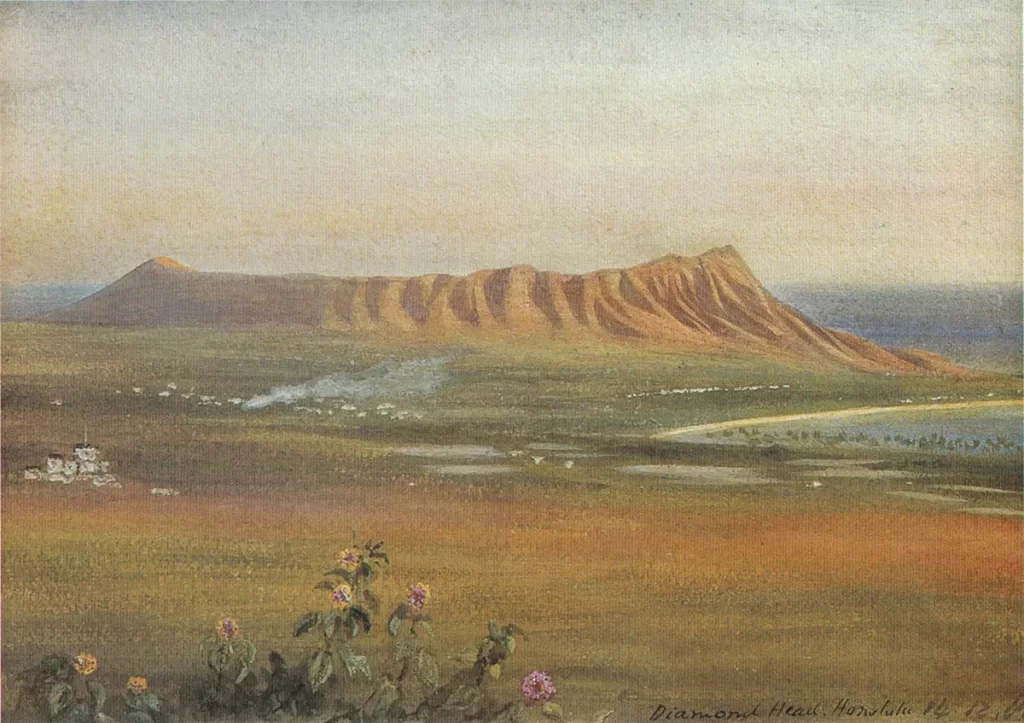

Long before Waikiki became a resort district, it was a low-lying coastal plain shaped by fresh water. Streams flowed down from the mountains. Springs surfaced near the shoreline. Large portions of the area existed as wetlands, fishponds, and agricultural fields rather than solid ground.

This earlier Waikiki supported intensive food production and dense human activity. Taro patches, fishponds, and settlement areas were spread across what are now some of the most developed blocks in Honolulu. Burial sites were interwoven with everyday landscapes, as they were throughout much of old Hawaiʻi.

When large-scale urban development began in the early twentieth century, the land itself had to be fundamentally altered. Wetlands were drained. Streams were diverted. Fill was brought in. The construction of the Ala Wai Canal permanently reshaped the hydrology of the area and made intensive building possible.

These changes did not erase what came before. They buried it.

Burials, Archaeology, and Modern Construction

Throughout Hawaiʻi, construction projects regularly encounter iwi kūpuna, ancestral human remains. Waikiki is no exception. Because of the area’s long history of settlement and cultivation, ground disturbance here often requires archaeological monitoring.

When remains are discovered, work typically stops. Specialists assess the find. Decisions are made about preservation in place, relocation, or other forms of treatment. These processes are governed by state law and cultural protocol, but they rarely become part of public storytelling.

For people who have lived and worked in Waikiki for long periods of time, it is widely understood that much of the neighborhood sits atop older Hawaiian landscapes, including burial grounds. This knowledge circulates more through lived experience and oral history than through plaques or guidebooks.

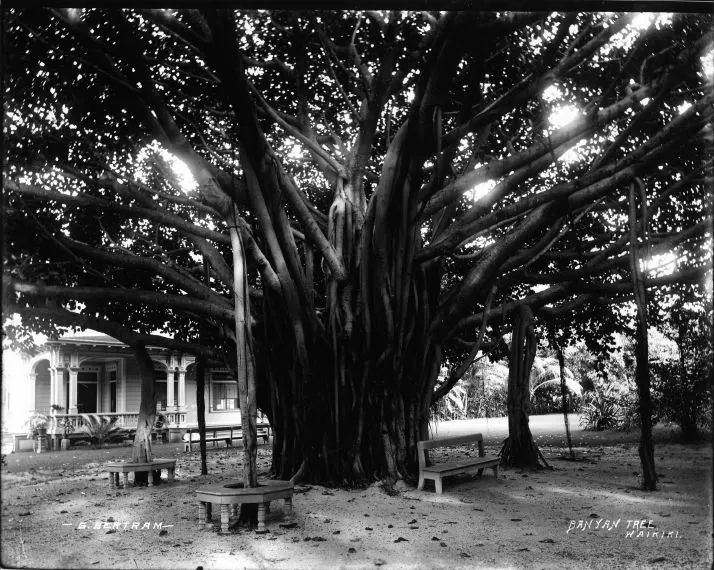

Still, the Trees Remain

Even as wetlands were drained, streets were cut, and towers rose, a small number of old trees remain rooted in the same ground they occupied long before Waikīkī became a resort district. Banyan trees, monkeypods, and other large canopy trees quietly mark continuity in a place defined by change. Buildings come and go. Sidewalks are replaced. Shorelines are reshaped. Yet some of these trees still stand where earlier generations once gathered, walked, and lived, offering a rare, living link between past and present.

A Built Environment Sitting on a Buried One

Modern Waikiki presents itself as polished and permanent. Concrete towers. Tiled sidewalks. Engineered beaches. But beneath that surface is a palimpsest. A place written over again and again.

Understanding this does not require assigning blame or invoking conspiracy. It simply means acknowledging that today’s landscape was created through large-scale transformation of an older one, and that traces of that older world remain physically present even if they are no longer visible.

A Brief History of Waikiki

Waikiki’s modern image can make it feel as if the neighborhood was invented alongside tourism. It wasn’t. Waikiki existed as a productive, inhabited landscape long before the first resort postcard. It had fresh water, fishponds, agriculture, and deep cultural meaning tied to the aliʻi and to everyday life.

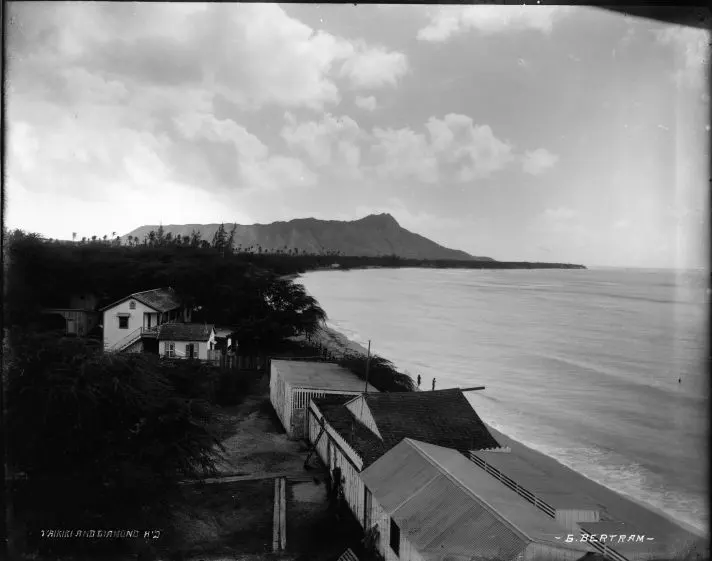

In the nineteenth century, Waikiki was associated with leisure and prestige, including royal retreat, while still remaining part of a wider network of Hawaiian land use and settlement. The coastline, the wetlands, and the inland plains formed a single system rather than separate zones.

The transition toward the Waikiki people recognize today accelerated in the early twentieth century. Large engineering projects altered the area’s hydrology and made dense urban construction feasible. Wetlands were drained. Streams were diverted. Fill was brought in. The construction of the Ala Wai Canal permanently reshaped how water moved through the area. Hotels followed. Streets were widened. Shoreline areas were reinforced and reshaped. What had been a low-lying wet landscape was converted into buildable real estate, setting the physical foundation for the resort district that would emerge over the decades that followed.

Modern Day Waikiki

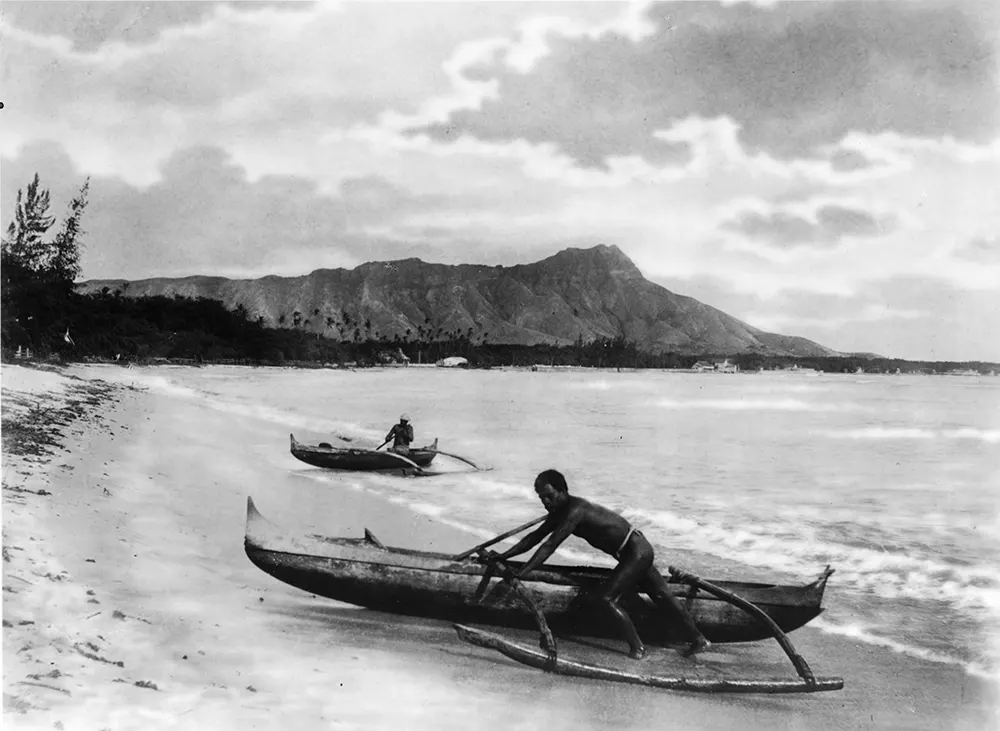

At the same time, Waikiki was becoming a stage for modern surf culture. Outrigger canoe clubs, beachboys, and high-profile figures like Duke Kahanamoku helped connect Waikiki to the outside world. Surfing became both recreation and symbol, and Waikiki became one of the key places where that symbol was exported globally.

After World War II, tourism intensified and the skyline rose. Waikiki transformed into a high-density resort district, but it never stopped being a lived environment. Residents remained. Local businesses adapted. A workforce moved in and out. The neighborhood’s identity became less singular over time, not more. Waikiki today is the accumulation of many eras stacked in one small coastal strip.

A Dense Mix of People and Purposes

Waikiki is one of the most demographically mixed neighborhoods in Hawaiʻi. Longtime local families live alongside recent transplants, international residents, seasonal workers, military personnel, service industry employees, and people who arrived with no long-term plan at all. Some came for opportunity. Some came chasing an idea of Hawaiʻi. Some simply never left.

This density creates a social fabric that is constantly in motion. People arrive. People leave. A smaller number stay. Relationships form quickly and dissolve just as quickly. The pace can feel transient, but beneath that churn is a core population that keeps the neighborhood functioning day after day.

A Working Neighborhood Disguised as a Resort

Behind the hotel facades and retail corridors is a large workforce that lives in or near Waikiki because proximity matters. Hospitality workers, restaurant staff, surf instructors, retail employees, healthcare workers, and building maintenance crews all rely on being close to where they work.

For many residents, Waikiki is not a playground. It is a practical choice shaped by walkability, bus access, and job density. The same sidewalks tourists stroll at night are the routes people use to commute before sunrise.

Multicultural by Reality, Not Marketing

Waikiki’s diversity is not a branding strategy. It is a product of history, migration, military presence, and Hawaiʻi’s position as a crossroads between continents. Hawaiian, Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, Korean, Pacific Islander, white, Black, and mixed-race communities are all part of daily life here.

You hear multiple languages on any given block. You see multiple cultural norms operating side by side. This coexistence is not always tidy, but it is normal. Waikiki reflects Hawaiʻi’s broader demographic reality in compressed form.

Surfing in Waikiki

Surfing in Waikiki predates modern tourism and outlives every trend that passes through the neighborhood. Long before surf schools, board rentals, and branded experiences, people rode waves here as part of everyday Hawaiian life.

What makes Waikiki distinctive is not raw power. It is consistency and shape. The reefs offshore break incoming swell into long, rolling waves that peel gently and travel far across shallow reef shelves. These conditions favor glide, trim, and flow rather than explosive maneuvers.

This is why Waikiki remains one of the most surfed coastlines on earth. It supports beginners, longboarders, instructors, and experienced surfers all within the same general zone. That overlap produces both opportunity and friction. Lineups here are crowded. Etiquette matters.

The Nature of Waikiki Waves

Most Waikiki surf breaks sit on reef rather than sand. The reef contours slow incoming swell and stretch waves into long, predictable shapes. On small days, this produces soft, manageable surf. On larger south swells, the same reefs can produce fast, powerful walls.

Water depth is generally shallow enough to make paddling easier than at many beachbreaks, but shallow enough to demand awareness. Falling incorrectly can mean contact with reef. This combination of friendliness and consequence is part of Waikiki’s character.

Historic Surf Breaks of Waikiki

Waikiki is not a single surf spot. It is a chain of distinct breaks spread along the shoreline, each with its own personality. Names have been passed down for generations, tied to reef features, nearby landmarks, or old usage.

Canoes

One of the most recognizable breaks in Waikiki. Long, rolling waves with forgiving takeoffs. Heavy longboard presence. Extremely crowded on most days.

Queen’s

Located near the Waikiki Aquarium. Softer, slower waves on smaller days. Used by a wide range of surfers from beginners to experienced longboarders.

Pops

Faster than Canoes with more push. Popular with progressing surfers. Can handle slightly more size.

Publics

Mixed peaks with shifting takeoff zones. Skill levels vary depending on conditions.

Threes & Fours

Two closely spaced reef breaks. Softer shoulders, long rides on small to medium south swells.

Tonggs

Classic Waikiki longboard wave with long, gliding rides. Can get crowded quickly.

Rockpiles

Heavier and faster than most Waikiki breaks. Generally favors more experienced surfers.

Surf Culture, Not Surf Industry

It is easy to mistake Waikiki surfing for a commercial invention. Board rentals on sidewalks. Lesson kiosks. Branded rashguards. That layer exists, but it sits on top of something older and far less transactional.

Surfing in Waikiki grew out of Hawaiian cultural practice and community recreation. It was embedded in daily life long before it was packaged as an activity. Outrigger canoe clubs, beachboys, and families surfing together formed the backbone of this coastline’s surf identity.

That lineage still shows. Longboards dominate. Many surfers favor trim, positioning, and wave count over aggressive performance. The emphasis is on glide rather than spectacle.

Lineup etiquette in Waikiki reflects this cultural inheritance. Patience, awareness, and respect matter more here than at many high-performance beachbreaks. Crowds are normal. Order emerges informally. People who disrupt that order tend to feel it quickly.

The result is a surf zone that can feel chaotic on the surface but surprisingly stable underneath. Waikiki does not reward ego. It rewards consistency, humility, and time in the water.

Weird, Overlooked, or Uncomfortable Realities

Waikiki’s public image is tightly controlled. The version most people encounter is clean, bright, and frictionless. That presentation requires constant maintenance, both physical and narrative. A great deal of what exists in the neighborhood does not fit neatly into that story.

Some of these realities are historical. Some are social. Some are simply strange. None of them cancel out Waikiki’s appeal, but they complicate it.

Built on Engineered Ground

Large portions of Waikiki Beach are maintained through sand replenishment. Sand has been imported, moved, and reshaped multiple times over the decades to counter erosion and storm damage.

What appears natural is often carefully managed. Groins, seawalls, and offshore structures quietly shape wave energy and sand movement. The beach is less a static feature and more an ongoing construction project.

Sacred Sites in Plain Sight

Within walking distance of umbrellas and surfboard rentals are sites with deep cultural and spiritual meaning. Healing stones, former temple areas, and places tied to ancient narratives exist quietly inside modern Waikiki.

Most people pass without noticing. Those who know tend to treat these places with quiet respect rather than spectacle.

Oral Histories and Local Lore

Stories circulate in Waikiki that never appear in official guides. Accounts of construction uncovering human remains. Reports of unexplained sightings. Legends tied to specific blocks or hotels.

Whether taken literally or symbolically, these stories function as reminders that Waikiki is not a blank canvas. It is a place with memory, and memory has a way of surfacing even when buried.

Tourism and Its Double Edge

Waikiki exists largely because of tourism, and it struggles because of it. Both statements can be true at the same time.

The visitor economy provides tens of thousands of jobs and sustains a massive portion of Honolulu’s commercial activity. Hotels, restaurants, tour companies, retailers, and service industries cluster here because demand is constant.

At the same time, heavy tourism places pressure on housing, infrastructure, and public space. Rents rise. Short-term rentals outcompete long-term tenants. Streets and beaches carry more bodies than they were ever designed to support.

For residents, this produces a complicated relationship with the industry that surrounds them. Tourism is both livelihood and burden. Pride and resentment often coexist.

Waikiki is not unique in this tension, but it may be one of the most concentrated examples of it anywhere in the world.

Waikiki as It Exists Today

Modern Waikiki is dense, vertical, and busy. Towers stack hotels, residences, and offices on top of one another. The sidewalks carry a near-constant flow of people. The neighborhood feels compressed, but it is also highly walkable.

Most daily needs exist within a few blocks. Grocery stores, pharmacies, gyms, medical offices, restaurants, bars, and small shops are woven into the same grid. For residents, this creates a version of city life where cars are optional rather than mandatory.

Public space remains one of Waikiki’s defining features. Beaches, parks, promenades, and open plazas act as shared living rooms for visitors and locals alike. This constant mixing is part of what makes Waikiki feel alive and part of what makes it exhausting.

Despite decades of redevelopment, Waikiki has not settled into a single identity. It continues to oscillate between resort, neighborhood, cultural site, and economic engine. The friction between these roles is not a flaw. It is the defining characteristic.

Experiencing Waikiki Through Surfing

For many visitors, surfing becomes the most direct way to interact with Waikiki beyond observation. It requires entering the water, reading the ocean, and participating in a rhythm that predates the resort district.

Some arrive with experience. Many do not. Either way, Waikiki’s wave character allows a wide range of people to engage with surfing in a relatively accessible environment.

Those who choose guided instruction typically do so not just to stand up on a board, but to shorten the learning curve and understand how to move through a busy lineup with awareness and respect.

Links to surf lesson and surf school pages can live here as a simple pathway for people who want to explore that option.

Why This Place Still Matters

It is easy to reduce Waikiki to its most visible elements. A beach. A skyline. A brand. But places do not become meaningful because they photograph well. They become meaningful because people continue to live, work, struggle, adapt, and build lives inside them.

Waikiki contains contradictions that never fully resolve. It is sacred ground and commercial ground. A home and a destination. A site of loss and a site of continuity. These tensions are not signs of failure. They are signs of history.

Understanding Waikiki does not require choosing a single narrative. It requires holding many at once. That complexity is what gives the place depth. Without it, Waikiki would be interchangeable with any other resort strip in the world. It isn’t.